A History of the Middle East Institute

George Camp Keiser, founder of MEI

In 1946, inspired by his experiences in the region prior to World War II, George Camp Keiser established a center for the study of the Middle East. An architect by training and a student of Islamic architecture, Keiser brought together a group of individuals who shared his interest in the region and his conviction that its importance in world affairs would only increase as the century progressed.

The group he assembled included a number of Washington’s most prominent scholars and statesmen: Christian A. Herter, a congressman from Massachusetts who would go on to become Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state and an advocate for the nascent concepts of global justice and the international rule of law; Ambassador George Allen; Harvey P. Hall, a former instructor at the American University of Beirut and Robert College in Istanbul; and Halford L. Hoskins, an academic who directed what would eventually become the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. Though their backgrounds varied, these men recognized how foreign policy was evolving. Together they wrote in a 1948 pamphlet that the very concepts of global strategy, security, and national interest would need “much reconsideration” in the post-war era. Nowhere, they argued, were these lessons more important than in the Middle East.

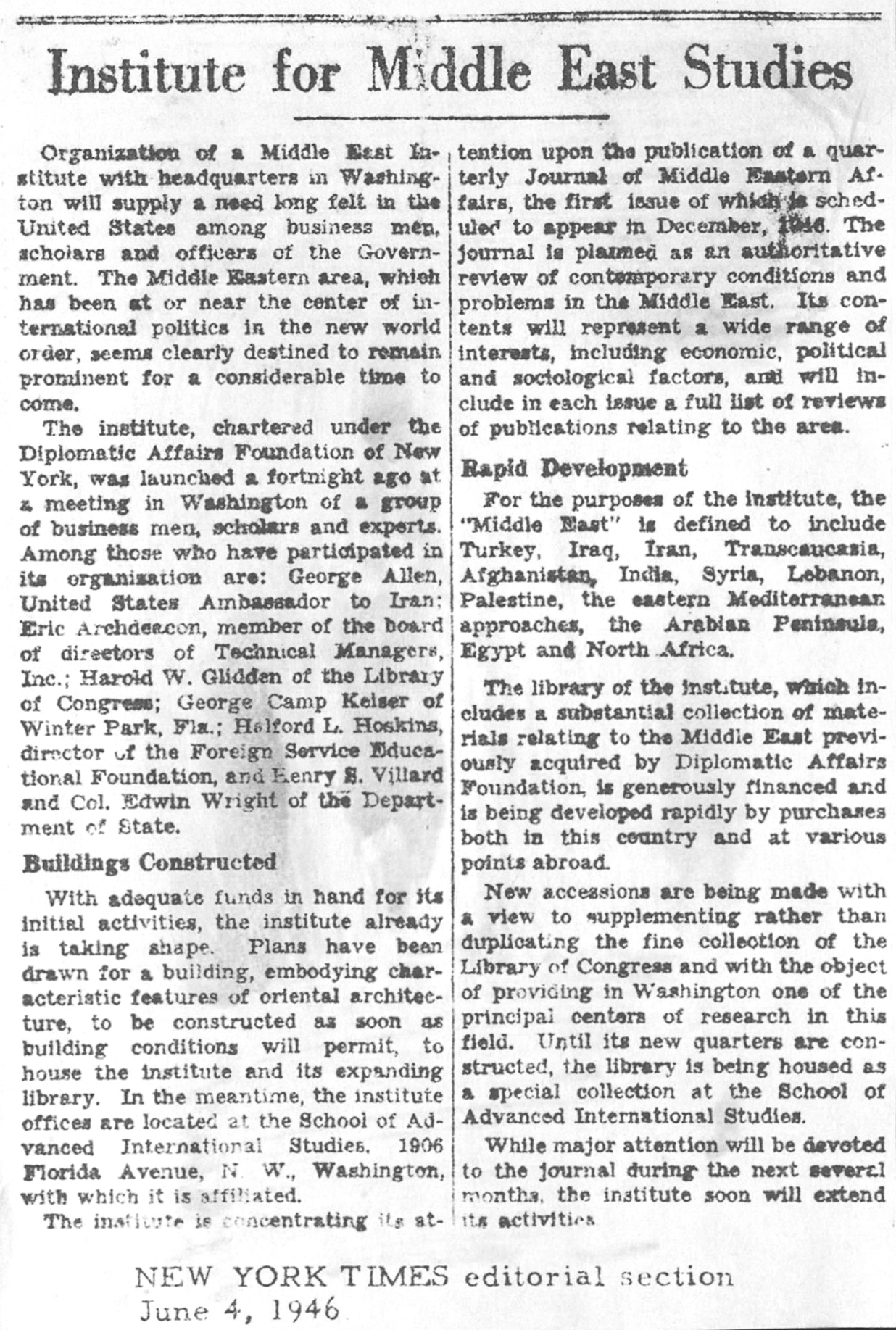

New York Times Announcement of the establishment of the Middle East Institute

Keiser and his colleagues envisioned a center of learning where leaders from disparate fields could converge and collaborate in order “to increase knowledge of the Middle East among citizens of the United States and to promote a better understanding between the peoples of these two areas.” This broad mandate was to be pursued through five specific means: a quarterly journal and other periodicals and books; a library dedicated exclusively to the Middle East and pertinent global issues; courses in the languages, history, cultures, religions, and politics of the region; research, writing, and publications by and for scholars in the emerging field of Middle East studies; and conferences and public lectures that would provide a forum for discussion of the region. In all of these pursuits, the Institute would commit to a position of political neutrality and attempt to deal objectively with a region in which facts have often been difficult to distinguish from legend and propaganda.

In its early years, MEI was an informal organization, more akin to a club for like-minded individuals than a scholarly institution. Its members met from time to time to discuss their travels in the Middle East, and an annual conference was held at the Friends Meeting House on Florida Avenue. This would change dramatically in the first few years after 1946. The late 1940s and early 1950s were a period of rapid growth for the Institute and by 1955, less than a decade after its founding, MEI’s membership had grown to over 500. The monthly newsletter, intended primarily for members and consisting largely of announcements regarding the Institute itself, evolved in 1953 into the Middle East Report, an illustrated magazine that appealed to a much wider audience. MEI began to publish books under its own imprint, the library expanded, and soon the Institute outgrew its original home. From a small office at 1906 Florida Ave, Keiser moved the organization to a temporary location on 19th Street, and finally to two adjoining townhouses on N Street near Dupont Circle, its home to this day.

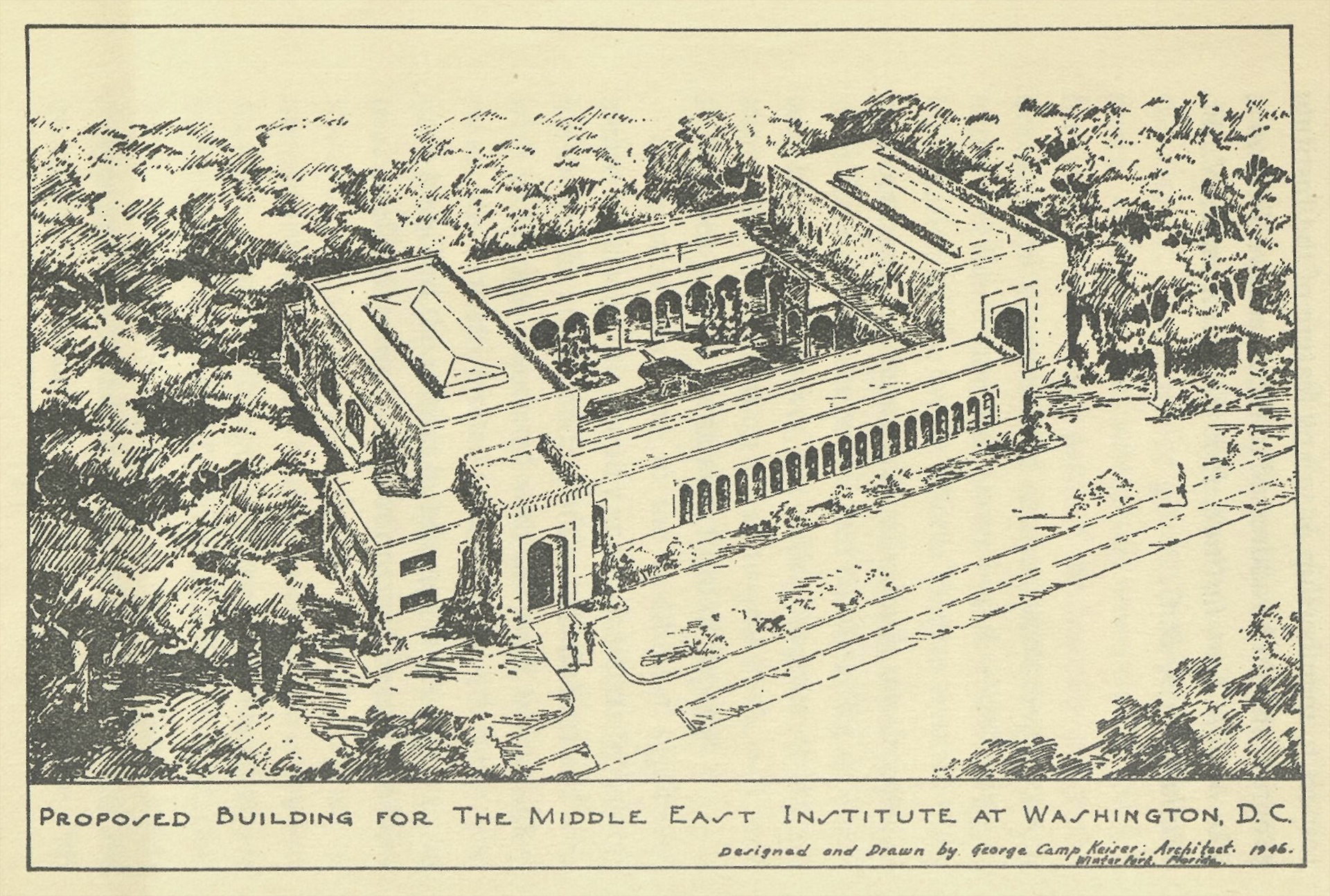

An early proposed design for MEI's headquarters drawn by George Camp Keiser in 1946. Though never constructed, the arched terraces are echoed in the rear courtyard of MEI's renovated office opened in 2019.

This rapid expansion of MEI’s programs outpaced the growth of its support base, and with the death of George Camp Keiser, the Institute lost not only its founding visionary but also its primary benefactor. Keiser’s death in 1956 left the Institute rudderless in the face of a mounting budget deficit. A series of part-time presidents, among them Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson Kermit, guided the institution through the ensuing 10-year crisis, struggling to keep Keiser’s vision alive. Despite their efforts, the budget crisis had a lasting impact on the organization. In 1961, the Board of Governors decided that MEI could not be sustained without significant downsizing. Its workforce was cut in half, and for the next several years the Institute operated with a skeleton staff of only five full-time employees. Dedicated volunteers and the support of neighboring institutions such as the Rockefeller Foundation and Georgetown University, which provided a free venue for the annual conference, kept the Institute afloat.

The Middle East Institute was founded 75 years ago on May 8, 1946. Join us in celebrating this landmark in MEI's history with a look back at some archival materials from its founding and early years.

Acutely aware of the challenges facing the organization, MEI’s Board of Governors sought new leadership. They settled on Ambassador Raymond Hare, who in 1966 was elected the first full-time president since Keiser. In his three-year tenure, Hare aggressively pursued a new vision for the Institute, first by consolidating and restructuring the significantly smaller organization, and then by concentrating on fundraising and cutting operating costs. He recruited student volunteers, solicited donations from members to expand the library, and doubled the number of corporate contributors in order to put the Institute on a more secure financial footing. By 1969, the Institute, now with over 1,000 members, was poised to enter a new phase of growth.

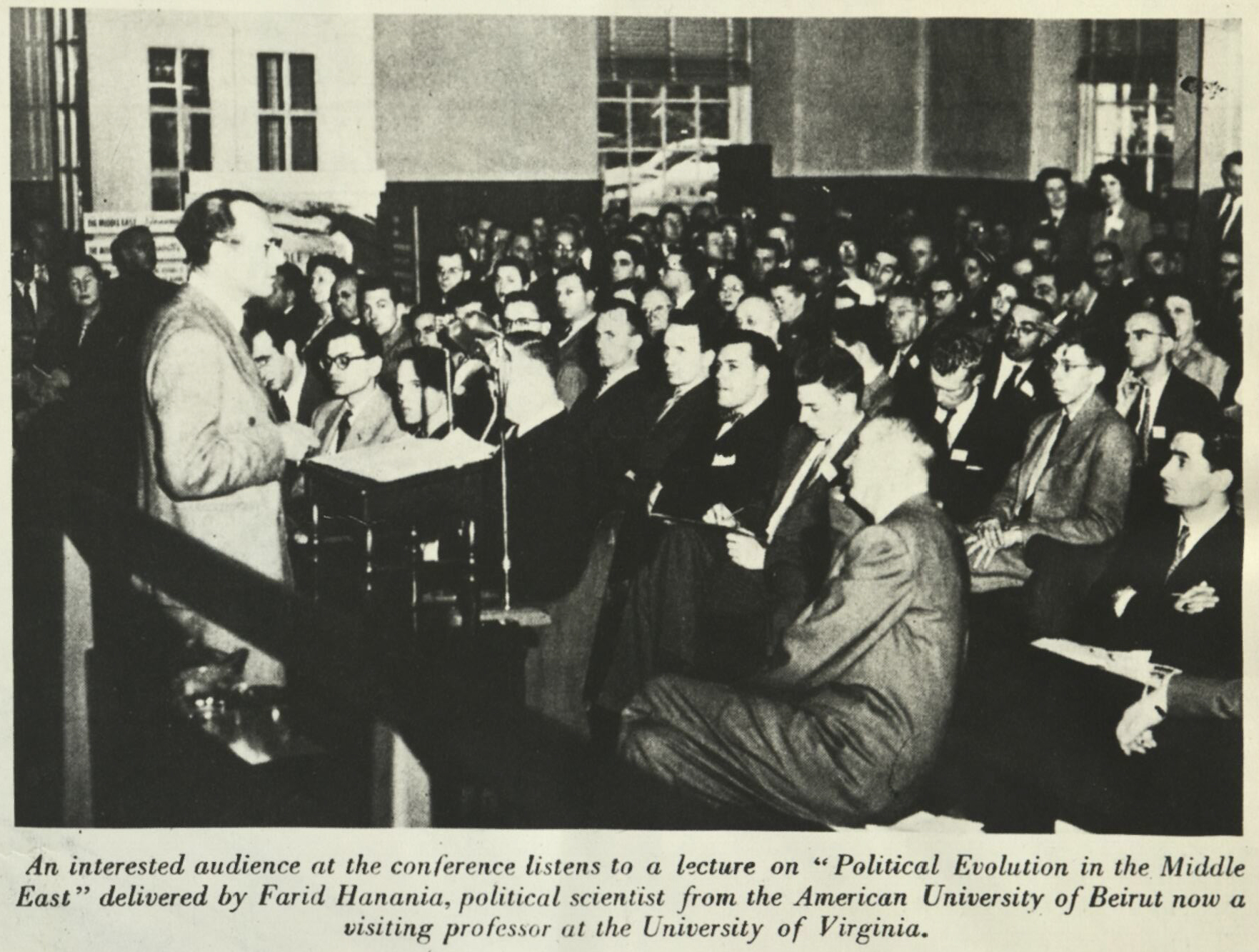

More than 500 Middle East diplomats, educators, US government officials and private citizens attended MEI's annual conference in 1953.

Ambassador Parker T. Hart, assistant secretary of state for Near East Affairs (a title held at different times both by his successor, Lucius Battle, and by Ambassador Hare), was elected president in 1969. What Hare did for the Institute’s finances Hart did for its vision. In the wake of upheavals at home and abroad, Hart introduced a suite of innovative programs to help establish MEI’s role as a facilitator of dialogue and an educator of non-specialists. Among these programs were a weekend retreat for Israeli and Arab students, a reinvigorated language program, and a series of new publications aimed at the general reader. In 1971, the Institute held its first annual Economic Seminar, a gathering of businessmen and investors interested in working in the Middle East, and in the same year helped to organize a series of “Arab-Western Dialogues,” panel discussions held in cities around the world.

The new president also continued the work of his predecessor in securing MEI’s base of financial support. Hart hoped to build an endowment for the Institute and, while ultimately unsuccessful, his fundraising drive did effectively double the operating budget, enabling the Institute to continue expanding its activities. A reaffirmed commitment to non-partisanship accompanied this effort, as Hart and the Board of Governors saw political neutrality as a core element of MEI’s identity. Neutrality had been essential to the Institute since its inception — the corporate charter explicitly excludes “attempting to influence legislation” from the Institute’s activities — and would become still more so throughout the 1970s.

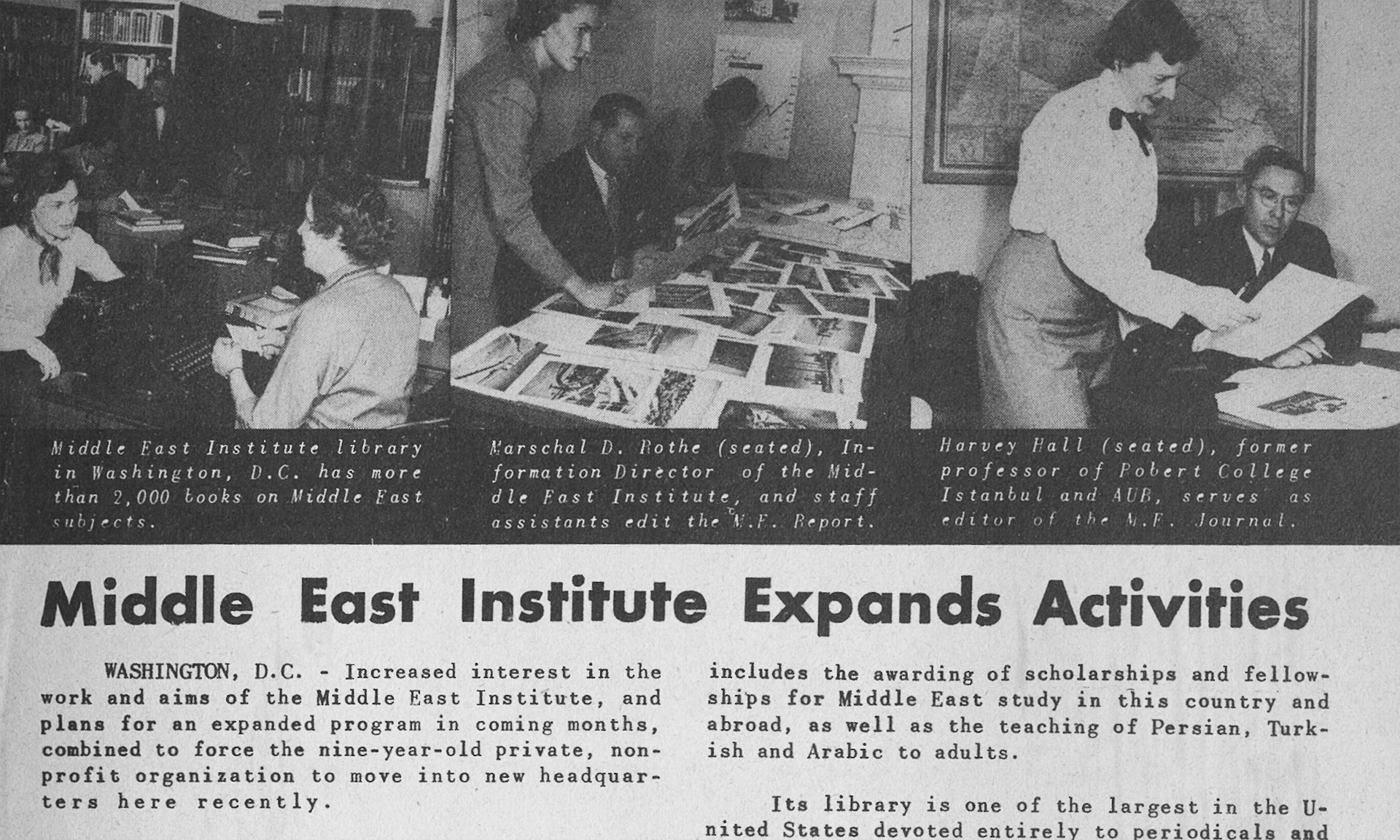

A 1955 announcement about MEI's relocation to larger headquarters, including photos of the Institute's Library and Harvey P. Hall, the first editor of The Middle East Journal.

Fueled by the 1967 and 1973 wars and later by the revolution in Iran, American interest in the Middle East was at a high point. With the addition of burgeoning Arab oil wealth, this led to a proliferation of publications, think tanks, and organizations dedicated to the study of the region. Where once MEI had been virtually the only institution of its kind, it now found itself in the company of numerous others. The American Enterprise Institute, Brookings Institution, and Center for Strategic and International Studies all turned their attention to the Middle East; Georgetown University entered the field in 1975 with the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies; and the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES) was established in 1970.

In this new context, it was crucial for MEI to find a more clearly-defined niche. A Committee on Plans, organized by Hart and charged with laying out the course of the Institute’s future, identified MEI’s well-established neutrality on political questions as one of the qualities that could set it apart from its neighbors. The Committee also pointed out that the Keiser Library, as it had come to be known, was a peerless resource for scholars and students, and that the Journal was written for the educated layperson, whereas the IJMES was intended for specialists. MEI was therefore ideally placed to operate as a source of publications and research that would complement, rather than compete with, the work of universities and of the Library of Congress; as an open forum for debate; and as a center of information for both specialists and the general public.

The institutional identity framed by the Committee on Plans guided MEI through the following decade. During the brief tenure of Ambassador Lucius D. Battle, the Institute earned a reputation as a reliable source of information among those with commercial interests in the Middle East, and published a popular series of Middle East Problem Papers intended to inform the general reader on the nuances of developments in the region. The Institute also enjoyed an increased media presence through the late 1970s and early 1980s — staff members were regularly featured on such popular outlets as “The Today Show” and various national news broadcasts, and published in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times.

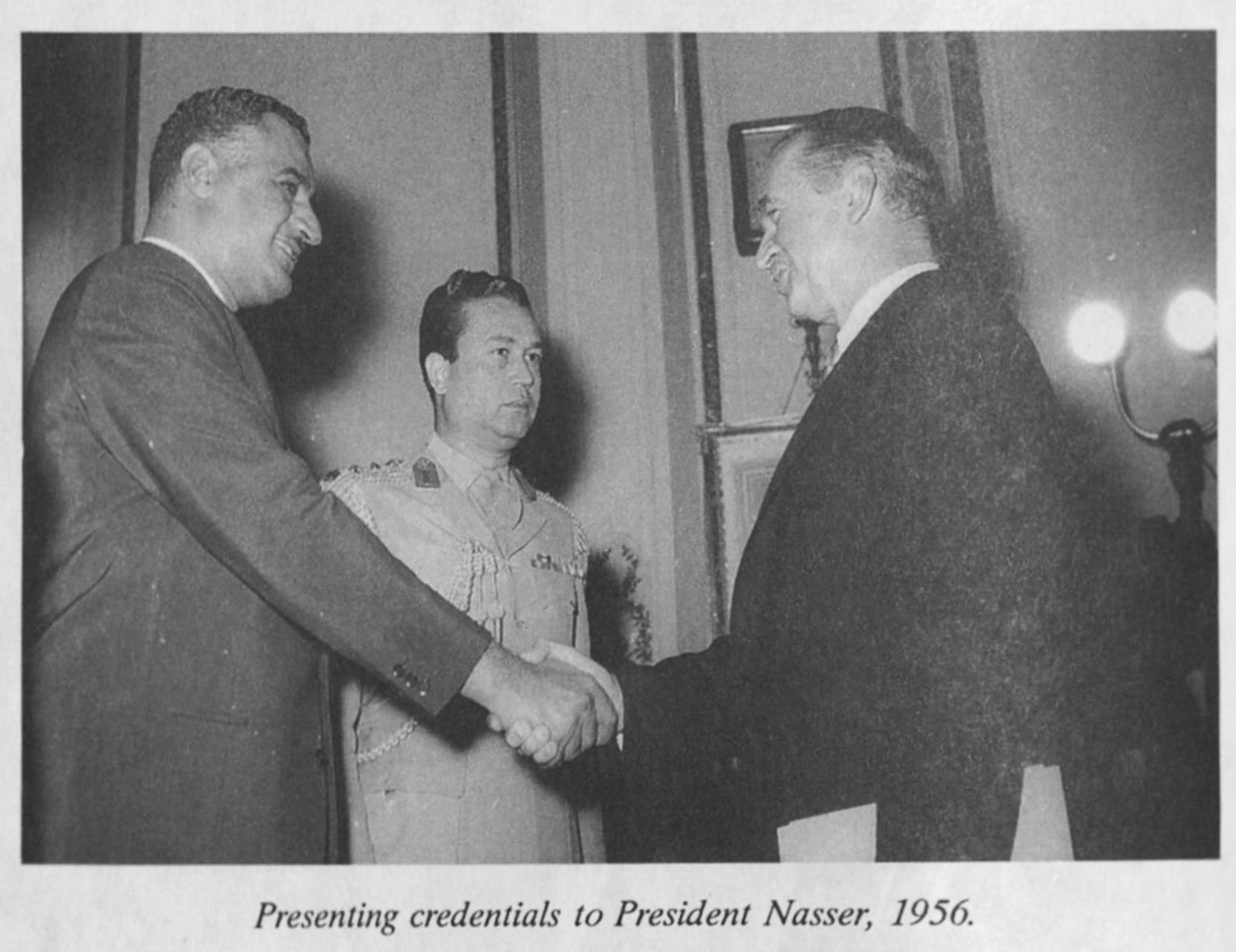

Amb. L. Dean Brown, later a president of MEI, and Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, 1956

In addition to raising MEI’s profile, this newfound visibility gave the Institute a platform for providing an American audience with accurate information and insights about the Middle East, a central element of its mission. The increased focus on public outreach was largely the work of Dean Brown, who presided over the Institute from 1975-1986, and who saw government, business, and media, rather than academia, as the primary constituencies of the Institute. Under his leadership, MEI continued its economic seminars, problem papers, and business-oriented conferences, and initiated new programs, including art exhibits and film screenings intended to bring encounters with Middle Eastern cultures to an American audience.

With public awareness of MEI at a high point, Brown saw an opportunity for a major fundraising initiative that would fulfill a longstanding wish of the organization. Since Keiser’s death, the buildings at 1761 N Street had been rented from his widow, Nancy. In 1981 she offered to sell the buildings to the Institute on favorable terms. Brown accepted Mrs. Keiser’s offer and raised enough money in just five years so that the mortgage was paid off in full by 1986. Additional funds came from a group of Omani entrepreneurs, celebrating the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Oman and the United States, who chose MEI as the best of many possible beneficiaries. Their gift enabled the Institute to renovate the dilapidated George Camp Keiser Library building, and was the seed money for the Sultan Qaboos bin Said Research Center, named for Oman’s ruling monarch, which in 2006 became the Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center (SQCC). Originally sharing office space within MEI, SQCC departed to establish its current headquarters on 16th Street in 2014.

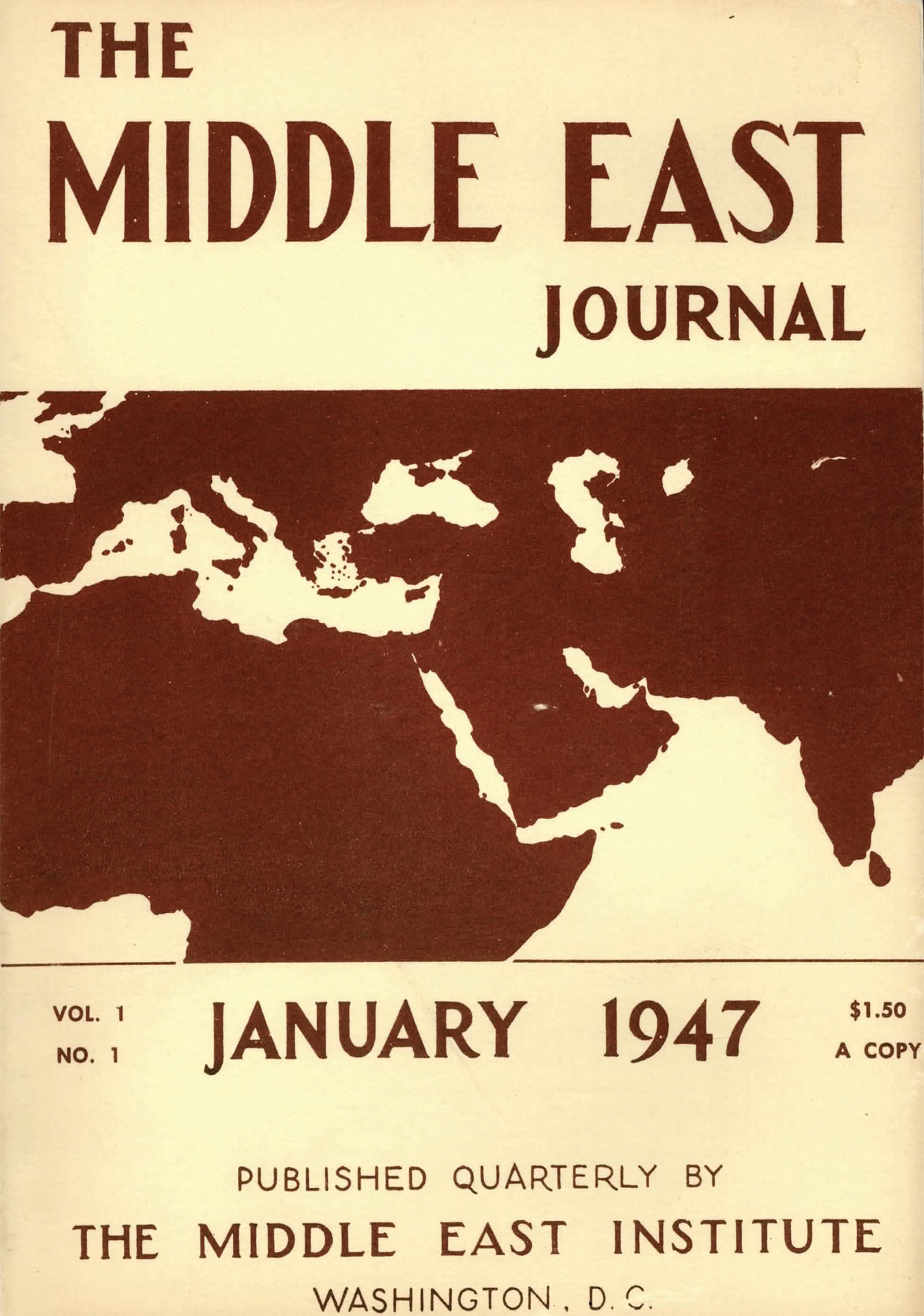

Cover of the first issue of The Middle East Journal.

This period of growth, of course, could not last forever, and in the early 1990s, MEI confronted its second major budget crisis. Financial constraints forced the Institute to streamline its programs; a decline in interest coupled with rising costs led to the phasing out of many of the cultural outreach programs that had begun under Brown’s leadership; the first Director of Development was hired so that fundraising activities would be concentrated in one office rather than shared among the entirety of the staff; and MEI narrowed its focus to target policymakers and businesses. In the half-century since the Institute’s founding, the field of Middle East Studies had developed into a major area of study supported by colleges and universities worldwide, and demand for MEI’s scholarly programs had declined as a result. While the Middle East Journal continued to be a fixture of the discipline — as the oldest and one of the most respected peer-reviewed journals on Middle East affairs — Brown and his immediate successors thought the academic community had less use for MEI than the business and government communities, which were not as well-served by other institutions. Their focus on policy-relevant work helped to increase the Institute’s efficiency, as did their embrace of digital technology. A website was built, records were digitized, and the library began the long process of replacing its card catalogue with a digital system.

The process of reorganization and updating through the 1990s enabled the Institute to emerge from its precarious financial situation, and by the year 2000 its budget was once again in the black. The budget surplus enabled a new expansion. MEI’s language classes, the Journal, and the annual conference grew to become its core activities.

From its humble beginnings, MEI’s annual conference and gala have become signature events among Washington’s Middle East policy crowd. Notable keynote speakers have included U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, President Bill Clinton, and Deputy Secretary of State and CIA Director William J. Burns. Since 2010, the Issam M. Fares Award for Excellence, endowed by the former deputy prime minister of Lebanon, has been awarded during the annual gala to inspirational, innovative Middle Eastern individuals who are making a difference in their communities and internationally. The Middle East Institute Visionary Award has recognized individuals and organizations for outstanding work in the region. Past recipients of these awards include Palestinian legislator, activist, and scholar Dr. Hanan Ashrawi; philanthropist Abdlatif Al-Hamad, director of the Kuwait Fund for Economic and Social Development; Mohamed A. El-Erian, prominent Egyptian-American businessman and economic advisor; and Lebanese award-winning filmmaker Nadine Labaki.

50's era newspaper ad for MEI language classes.

The 2000s saw an increased emphasis on MEI’s academic services. The Institute’s language department, which offers instruction and private tutoring in Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, Urdu, Pashto, and Dari, gained national accreditation in 2005, a validation of the high quality of teaching offered under the Institute’s auspices.

MEI launched its Turkish Studies and Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies centers in 2009 under the leadership of President Wendy Chamberlin, a former U.S. ambassador to Pakistan. The centers sought to attract scholars from around the world and provide a source of expertise and information for students and the media on two areas of major geopolitical importance to the region. They also formed the blueprint for the Institute’s future regional and topical research programs.

The Arab Spring uprisings that swept across the region in 2011 spurred a new set of challenges that are still reverberating a decade later and sharply increased demand for greater understanding of the region’s social, economic, and cultural dynamics. To seize this opportunity, the Institute launched a multi-faceted project focused on “Arab Transitions,” receiving funding to hire additional high-profile experts, significantly increase its publications output, and upgrade its website. This marked the beginning of a period of rapid expansion that included the creation of new staff positions, grant-funded programs, technological upgrades, and a greater emphasis on multimedia for reaching wider audiences.

In 2016, MEI made its first appearance in “The Global Go-To Think Tank Index Report,” an annual ranking of more than 11,000 organizations published by UPenn’s Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program. Initially ranked #72 among the list of “Top think Tanks in the US,” the Institute improved its ranking in each of the next five consecutive years, most recently ranking #31 in 2021. Today it is the top Middle East-focused policy institution in the United States, and ranks among the top 1% of think tanks globally.

In February 2017, MEI began a major two-year renovation and expansion of its historic brownstone headquarters. The long-envisioned project was made possible by a generous donation from the United Arab Emirates. During construction, the Institute’s staff and scholars relocated around the corner to temporary offices at 1319 18th St. NW.

The Institute was also embarking on a significant internal restructuring during this period, organizing its growing array of programs and services under three pillars: Policy, Education, and Arts & Culture. The Policy Center, the “think tank” side of MEI, expanded the number and breadth of its research programs, including ones focused on additional countries and regions, defense and security policy, issues of global concern such as climate change and conflict resolution, and the Middle East’s relations with other regions of geostrategic importance. The Education Center increased its course offerings to include regional studies classes in addition to both group and private language tutoring. And the Arts & Culture Center expanded its programming to include exhibitions, film screenings, and musical events, in addition to its core panel discussions at the intersection of art and policy.

In July 2018, Ambassador Wendy Chamberlin retired after nearly 12 years as president of the Institute and Paul Salem, previously MEI’s senior vice president, was appointed to serve as its new leader.

On September 12, 2019, MEI held a ribbon-cutting ceremony officially opening its fully renovated headquarters. Visitors now enter the building at 1763 N Street to find themselves in the new MEI Art Gallery, a showcase for the region’s contemporary and modern art, photography, and video. The Gallery, operated by the Institute’s Arts & Culture Center, displays up to four exhibitions a year, supplemented by public programs and events.

MEI President L. Dean Brown with Egypt's First Lady Jehan Sadat at launch of MEI cultural program, 'Egypt Today,' 1981

The downstairs entrance at 1761 N Street now leads to the MEI Education Center, which was expanded to occupy the entire first floor of the Institute. The Center oversees the Institute’s academic services including language classes and tutoring, regional studies courses, the Oman Library, and the Leadership Development Program for interns and research assistants. After an extensive restructuring process, the Center regained national accreditation for language instruction in April 2020.

Just a few months after its grand reopening, the global COVID-19 pandemic forced the Institute’s work and programming to move online while staff and scholars worked from home. In-person events, meetings, and conferences were replaced by webinars; language classes and tutoring were conducted over video conferences; and the MEI Art Gallery and Oman Library were temporarily closed until limited visits could be scheduled safely. The gallery organized its first virtual 3D exhibition in response to the short-term closure. And, for the first time in its history, MEI’s annual conference was held virtually.

As MEI marks its 75th anniversary year, its growth has eclipsed expectations. At the time of this writing, the Policy Center features 18 research programs and has grown from 40 scholars three years ago to over 150 today. It is convening more high-level policy events than ever before; its virtual events feature more regional voices and attract larger, more international audiences than in the past. It’s publishing more books and articles and serving more students and professionals through its online courses. And the MEI Art Gallery, once again open to the public, continues to educate audiences about the region’s rich culture.

George Camp Keiser’s vision has continued to provide inspiration for successive generations of the Institute’s leadership, scholars, and staff as MEI has grown rapidly into a world-class think tank, educational center, and cultural institution. Seventy-five years after its establishment, MEI’s reputation for non-partisanship, excellence, and integrity has translated into real impact as it works to advance a stronger US-Middle East relationship.

As a leading American organization focused on the Middle East, MEI is leveraging its history and legacy by launching MEI@75, a three-year campaign to deepen and expand our work towards building the US-Middle East relationship.

اقرأ المزيد